From Wisconsin to Wasabi: How I Became the Last Traditionally Trained Sushi Chef

A wild ride through immigration policies, knife-sharpening, and the questionable wisdom of a 20-something white guy"

History repeats itself. We are living in the craziest of times—planes crashing, the EPA dissolving, walking away from the WHO, and whatever fresh hell is happening with ICE. But back in the mid-'90s, California made a bold immigration policy shift: if you were in the country illegally and left by a certain date, all would be forgiven. No penalties, no repercussions—just a clean slate, assuming you actually left.

As a white guy from Wisconsin, this policy didn’t exactly rock my world. But at the time, I was working at a sushi/teppanyaki restaurant, where most of the Japanese staff had overstayed their visas and were, shall we say, living on the edge. Meanwhile, the Latino kitchen crew in the back barely batted an eye at the new law. It was just another day for them.

One night, the “crew” from the sushi joint—chefs, waiters were out drinking and laughing, as was tradition. But there was an undercurrent of stress. A couple of the Japanese sushi chefs were feeling the weight of this policy. They wanted the option to go home to Japan, visit their families, and return to California. But if they stayed past the deadline, they’d be banned from coming back. The restaurant itself was in crisis—half the sushi chefs might be leaving, and everyone was panicking.

And then, in my drunken, naive, 20-something wisdom, I declared, “How hard can it be? It’s not like only Japanese people can be sushi chefs.”

Silence. A record scratch, if you will.

At the time, the idea of a non-Japanese sushi chef was almost unheard of—A white guy. WTF. I even asked why there were never any female sushi chefs. The prevailing belief was that women’s body temperatures ran higher and fluctuated throughout the month, supposedly making them less suited for handling delicate raw fish. Because, naturally, sushi required the cold, unfeeling hands of a Japanese man. Flawless logic, right?

As I write this, I can’t help but wonder: was this the moment we started losing our grip on integrity, on tradition, on the sacred codes of society? Did I, a clueless white dude, crack open the door that led to the absolute fucking dumpster fire we’re living in today?

FUCK ME.

The room stayed quiet for a second. Then, all eyes shifted to Tanaka, our head sushi chef.

Ah, Tanaka. The man, the myth, the legend. The guy who had a deeply disturbing fetish for microwaving vegetables and...doing things to them.

He took a long, cinematic drag from his cigarette—full Yakuza style—exhaled, and muttered, “Baka.”

Idiot.

The whole table erupted in laughter.

But I was full of liquid courage and, more importantly, didn’t understand the intricate web of Japanese hierarchy and protocol. “No, really. I can do it. Just train me.”

More laughter. And then, just like that, the conversation shifted back to immigration policies and what the hell they were going to do about the restaurant.

Despite the absolute circus that was our workplace, the Japanese guys still lived by their country’s unspoken codes and ethics. Sure, they dabbled in SoCal’s carefree lifestyle, but at their core, they remained loyal to the traditions of the motherland. There were rules. There was respect. And in my drunken arrogance, I had just trampled all over them.

Monday morning, I showed up in my usual waiter uniform—dark pants, white shirt, tie, black shoes—ready to start the lunch prep.

Tanaka spotted me immediately. “You late.”

I blinked. “My shift starts at 10.”

He scoffed. “You training now. You must be here at 9. One hour late, BAKA!”

And that is how it began.

Tanaka took me under his wing. I was to train underneath him for three months before I could do anything. I was trained in a very traditional Japanese way—by watching. No hands-on practice, just silent observation. I sharpened everyone’s knives, cut seaweed to the exact specifications for rolls, ensured each chef had everything they needed at their stations, and fetched fish from the freezer for them to portion.

And Crean, crean, crean. “You have to Crean everyone’s station at end of night.”

I took a certain amount of pride in my training. I was going to be the last person to be traditionally trained in the ways of a real Japanese sushi chef. When Tanaka eventually left to return to Japan, he would take his traditions and experience with him, leaving me with the weight of that legacy.

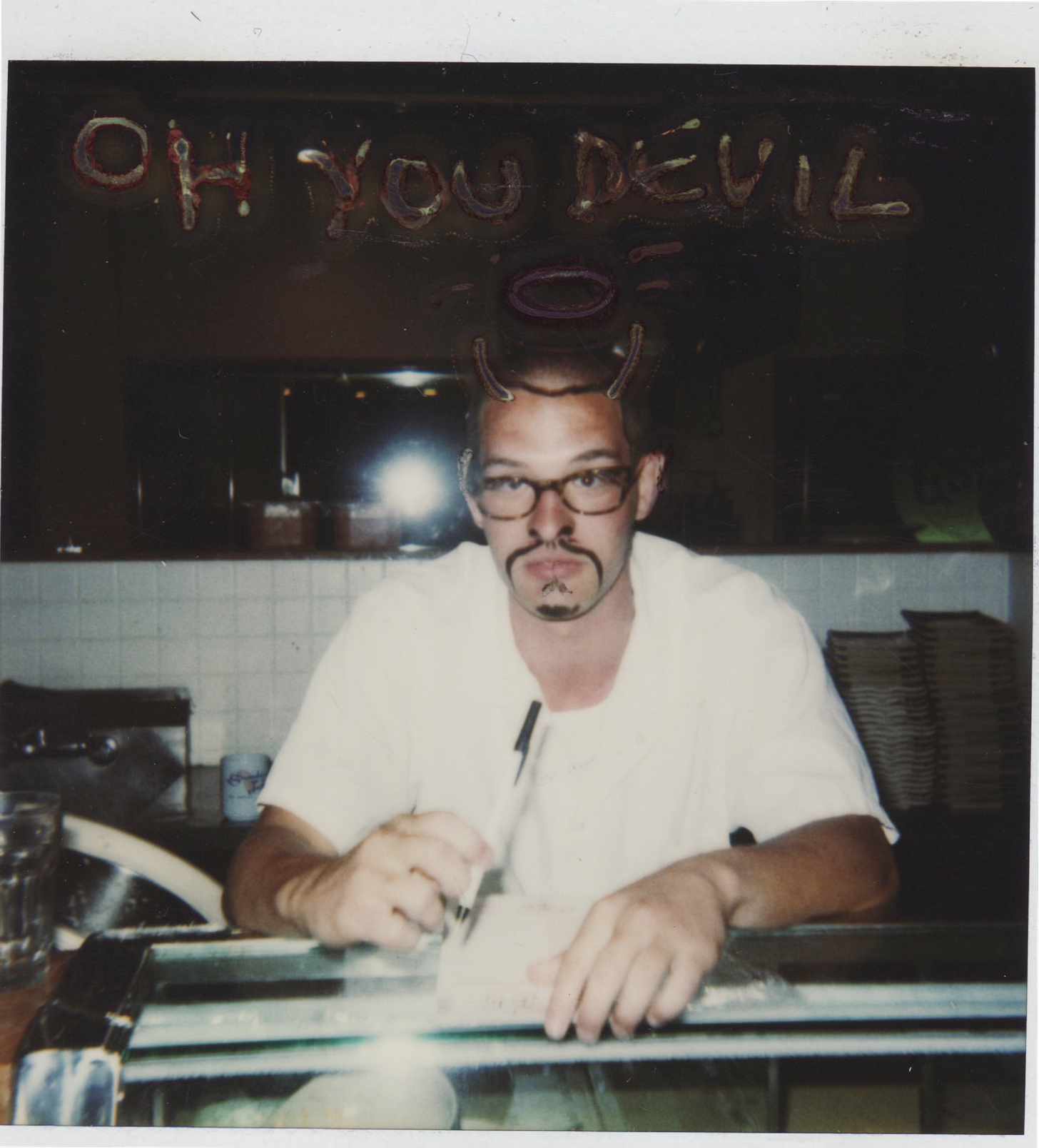

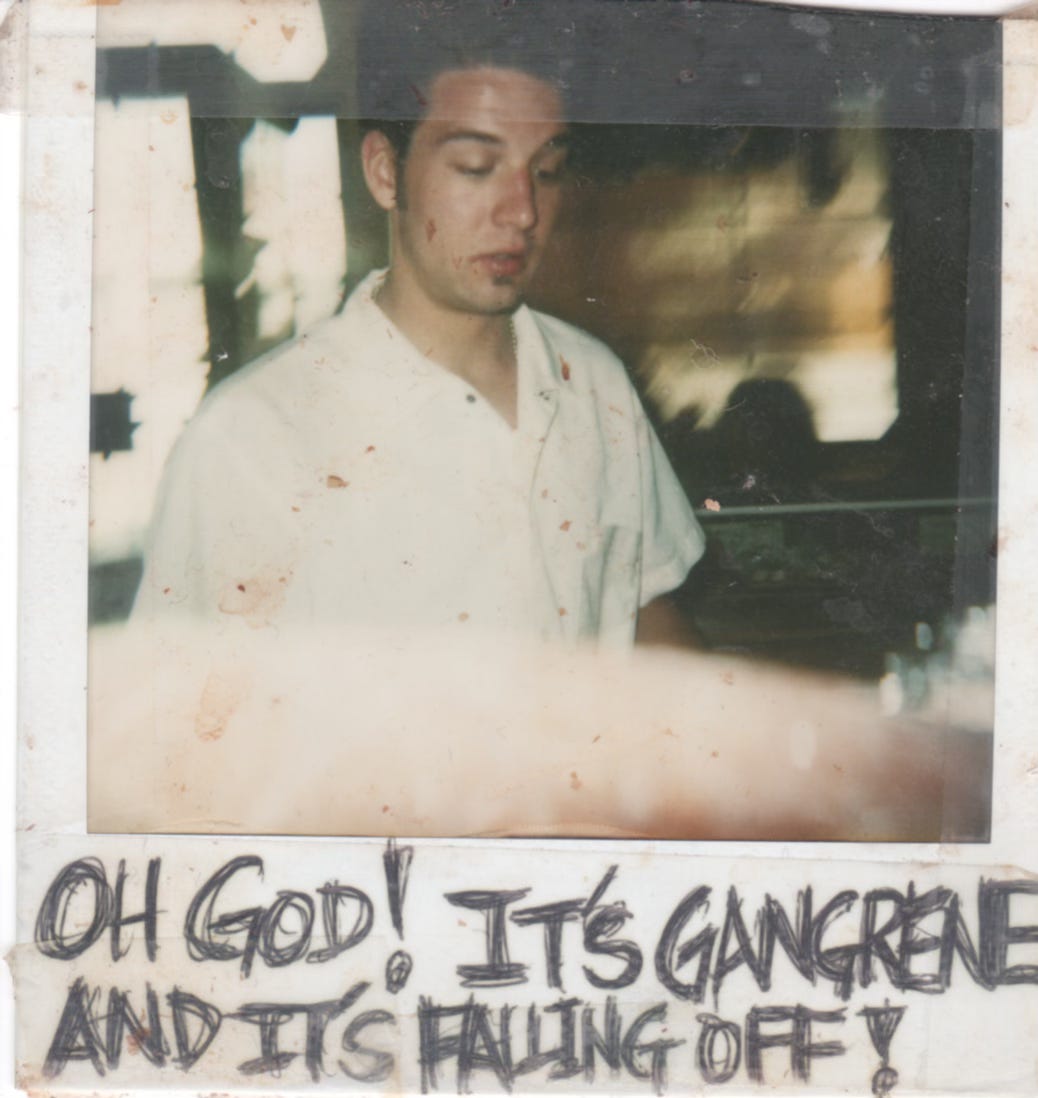

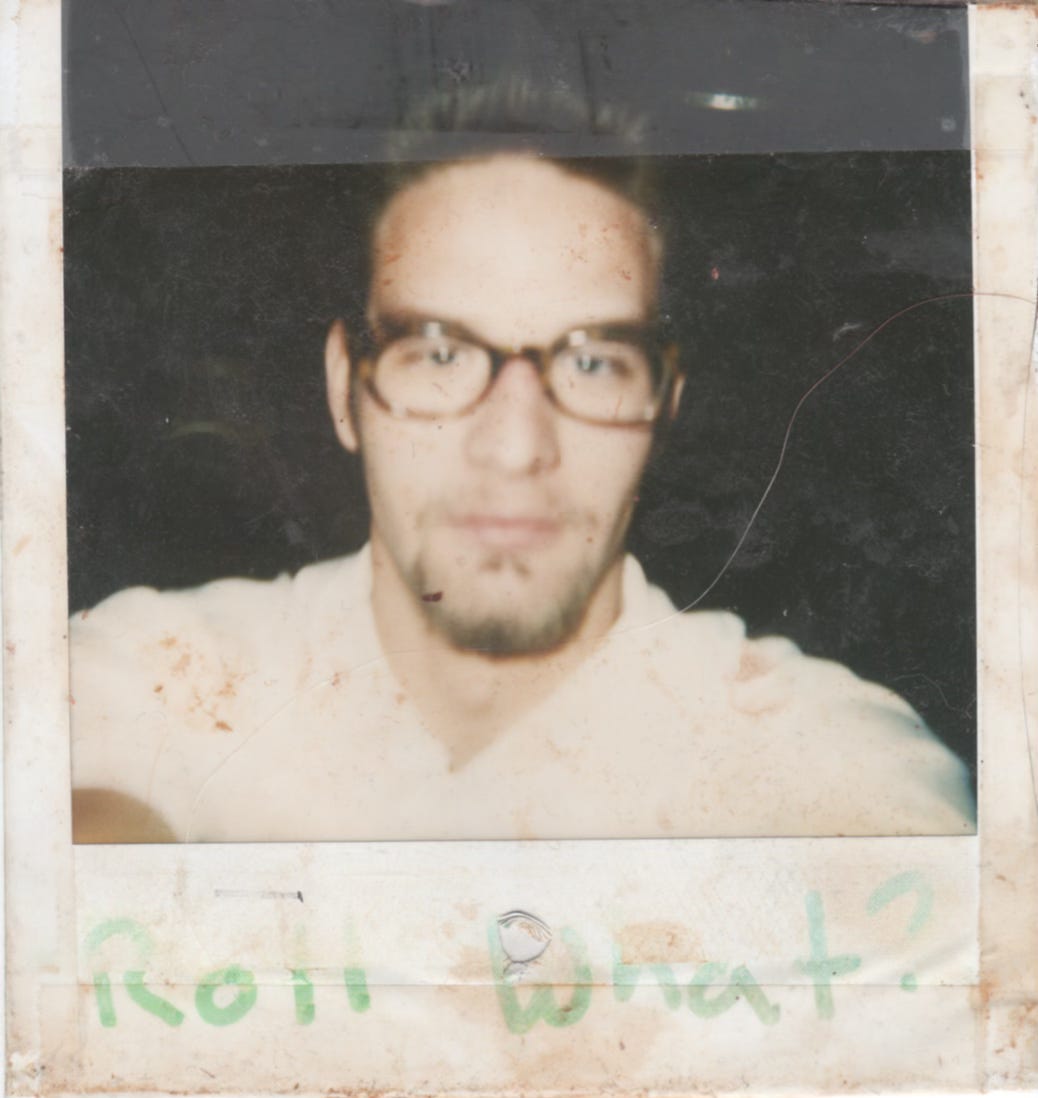

These Polaroids are what the sushi chefs would tape to the front of their seaweed boxes at their stations to mark ownership. I worked hard, I took pride in my training. After about two months, Tanaka started letting me work slowly with customers. I made simple rolls—California rolls, spider rolls, and anything else straightforward. Over time, I was trained to cut fish properly at the perfect angle for nigiri and sashimi.

That’s not to say I was above some occasional “mistakes”—screwing up just enough so I could eat it or share it with the waiters.

Finally, I was out at the station. Here’s a little insider tip: when you go to a sushi bar, the guy in the middle is the head chef. The ones on the ends? They’re still learning. If you want the best experience, sit in front of the middle guy. He’s the one making sure everything runs smoothly—both at the bar and for the tables.

After about a year and a half, many of the original Japanese sushi chefs had left. Immigration policies were tightening, and they didn’t want to risk being stuck in the U.S. or unable to return. For a time, it was just me, TO, and HG running the restaurant.

Can you imagine? The inmates running the asylum.

But somehow, we had that place dialed in. I was the last person to be traditionally trained, and before I knew it, I was the one training new chefs. I can only imagine how it looked—some white guy teaching the Asian guys how to make sushi and run the bar. Life is weird.

Looking back, I realize I wasn’t just learning how to make sushi—I was learning about culture, discipline, and respect. The weight of that training stayed with me long after I left the sushi bar.

Tanaka would probably roll his eyes if he saw me now, reminiscing about those days. But he gave me something I never expected—a crash course in a world I never belonged to, yet somehow became a part of.

And to this day, every time I sharpen a knife, slice through a piece of fish, or see a roll that’s been made with a little too much hesitation, I hear his voice in my head.

“Baka.”

Love & Light;

MM

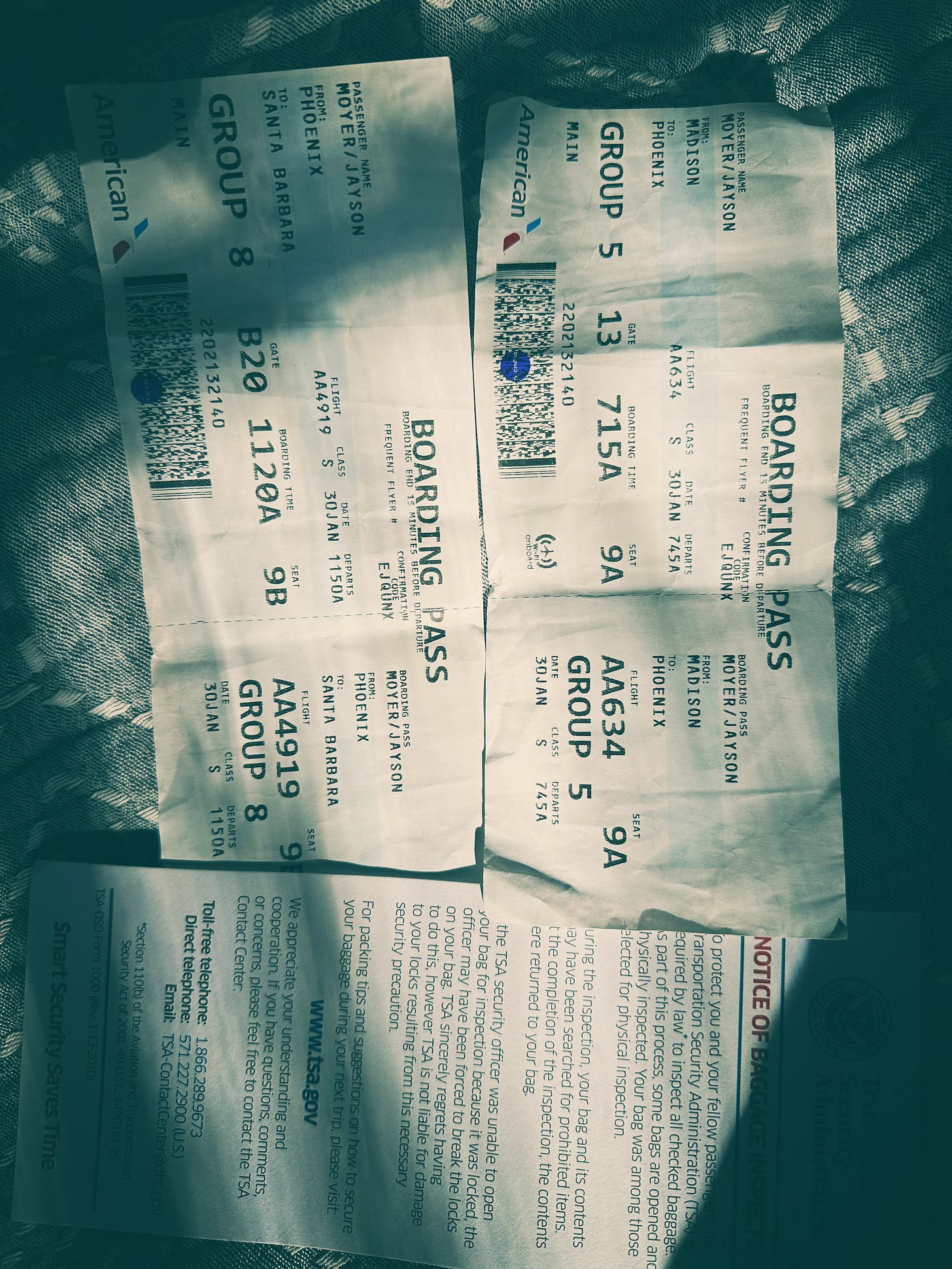

I made it back to SB and will have some fun post in the very near future.